Kiro’s in Private Preview. I Tried It—and I’m Not Using It Again.

Spec-to-ship sounds great. Without personas, context hygiene, or model choice, Kiro feels more like a demo reel than a dev tool

Kiro is currently all the hype of the agentic world. It’s a cursor-like IDE experience that’s designed fundamentally around documentation generation to produce resulting code. When I got access to it last night, I had to try it out to see if it was a step-function change above claude-code. So I put it to the test to develop a new feature from scratch.

But before I get into my take, some background: we have been using agentic IDEs for a hot minute (copilot then cursor then claude-code). The move to claude-code (CC) was the real game-changer for us. I remember that first command-line boot sequence of CC fondly because we gossiped like giddy teenagers about how magical it was. The phrase we kept coming back to was that it felt like the “iPhone moment” for agentic development — where our roles had fundamentally shifted from being “main-loop engineers” to that of mere copilots.

But after the first week or so, we realized that making CC a truly 10X tool necessitated adapting our workflows and building abstractions to have it produce valuable outputs (not just AI slop).

The key discovery we made was that writing good requirements documents was crucial to having claude-code produce useful outputs without constant back-and-forth.

So, when Kiro was revealed, architected entirely around addressing the challenge of producing crisp and precise design documents before a code generation handoff, we immediately imagined that it would be even better than claude-code.

Putting Kiro through its paces

To see how it would compare to my current development workflow with Claude-Code, I put Kiro to the test by tasking it to develop a new feature from soup-to-nuts for an opensource MCP server we released named mcping-mcp — an MCP that lets a client call a tool that sends desktop push notifications on OSX.

Goal: add a “schedule notifications” to have the MCP store and send desktop notifications for an arbitrary date-time in the future.

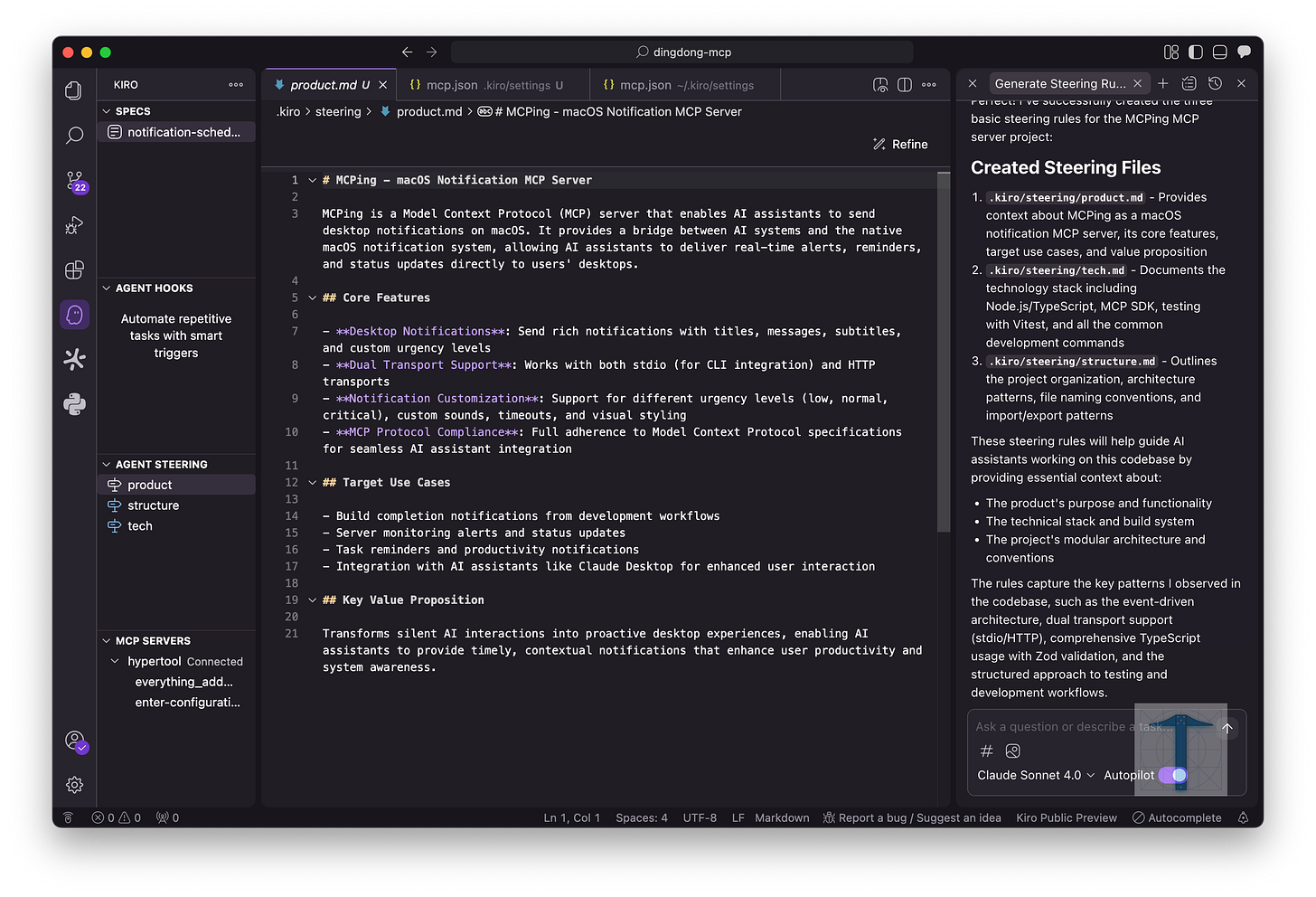

Phase 1: setting up the kitchen

To get Kiro rolling, it required the generation of Steering Documents — a product spec, a tech stack doc, and a structure doc. Think of these as a “split-up” CLAUDE.md that you might generate. The purpose of these artifacts is to give Kiro a guide on how to traverse and understand the major components of the project.

Product document → defines the product spec and “what it even is.”

Tech document → captures stack, libraries, SDKs, etc.

Structure document → outlines project structure and overall architecture pattern.

While this is a nice, polished workflow to scaffold context, it’s not revolutionary. In CC, we produce similar steering documents by having CC generate its own CLAUDE.md or by using tools like superclaude to generate structured document types like an ARCHITECTURE.md.

Recently, we’ve been using our own home-grown “steering framework” — more on this in a future post.

By default, these steering documents get injected into every Kiro model call unless you spend time crafting matcher rules for when a steering document should get pulled into a context. That means unless you proactively maintain a complex ruleset, you’re effectively dragging the entire bundle of product/tech/structure context into every generation. The cost is twofold: context pollution (irrelevant details bleeding into the context window) and token exhaustion (larger projects chewing through capacity fast).

The result of this design choice is that scoping is structural and not persona-driven. Rather than having persona-specific subagents — like a “QA engineer” or a “DevOps engineer” with fresh, clean contexts as Claude Code offers — Kiro defaults to an “omnipotent” agent that is expected to know every operating context.

takeaway: Kiro’s steering document generation is a nice polished IDE experience but its structural rather than persona-driven context approach is limiting and will lead to context pollution and poor generation.

Phase 2: let’s get cooking

Ok enough about steering documents. I was excited to get into seeing how it took requirements, came up with a design, and started biting away at the tasks.

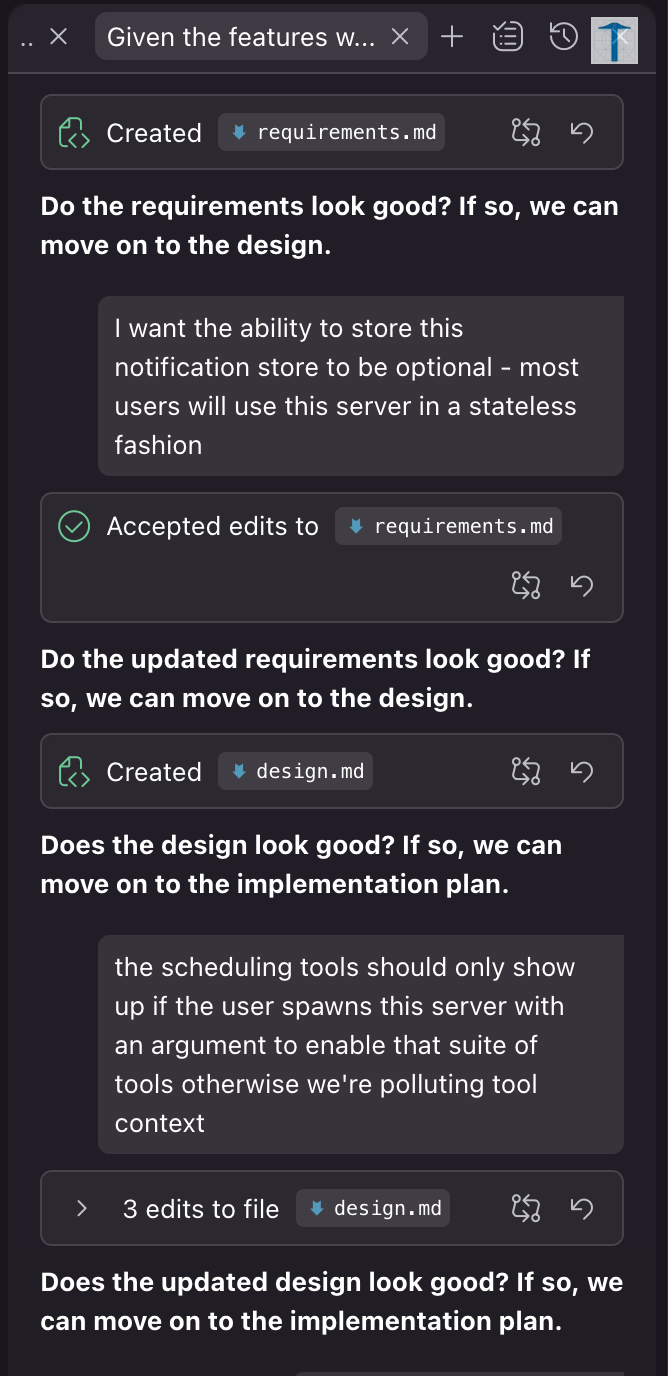

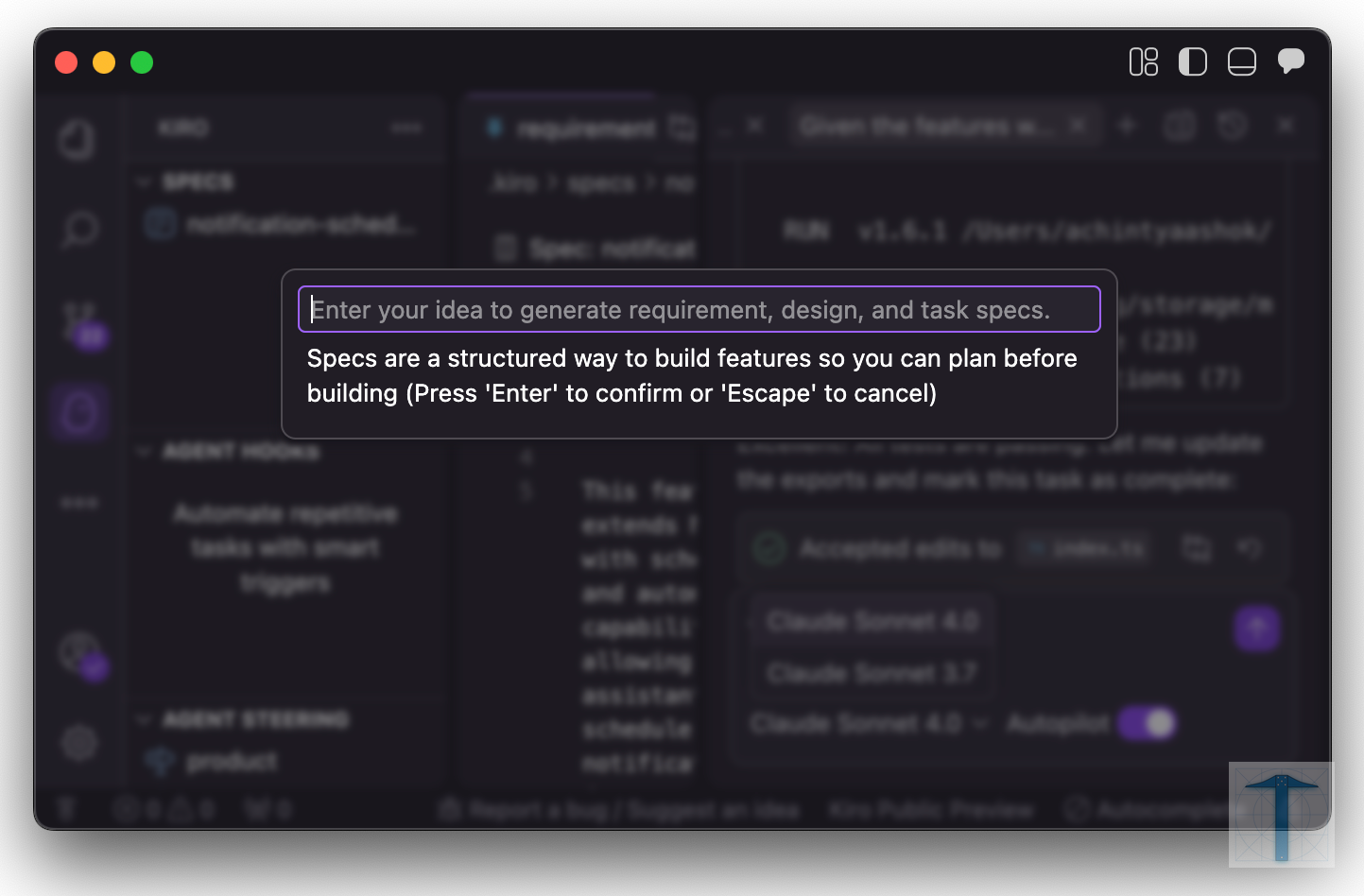

I began by handing it off the simple goal we outlined earlier: “add a “schedule notifications” to have the MCP store and send desktop notifications for an arbitrary date-time in the future.”

What I expect to happen at this point was for Kiro to go through a “20-questions” briefing with me to extract out the key elements of my requirements. Instead, it went immediately into generation mode without any further inputs.

In the span of a few seconds, it generated a massive requirements document in a monolithic generation adding user stories, edge-cases, and acceptance criteria. At the end of the generation, it immediately began prompting me to move onto the “design” phase. This eagerness to dive into the next phase made me feel like requirements gathering were being treated as a checkbox, rather than a critical phase.

This was probably the most disappointing interaction in my Kiro experience so far.

Kiro was supposed to be a better way to generate requirements. I fully expected it to be a conversational, socratic experience — like a white-boarding session with a teammate to come up with a draft. Instead, it ran with a “one-line vibe” and dove immediately into design and task generation.

Drafting requirements before moving onto design is the single-most leveraged part of agentic flow — if you get this wrong, every downstream step devolves into AI slop (design —> task generation —> code generation).

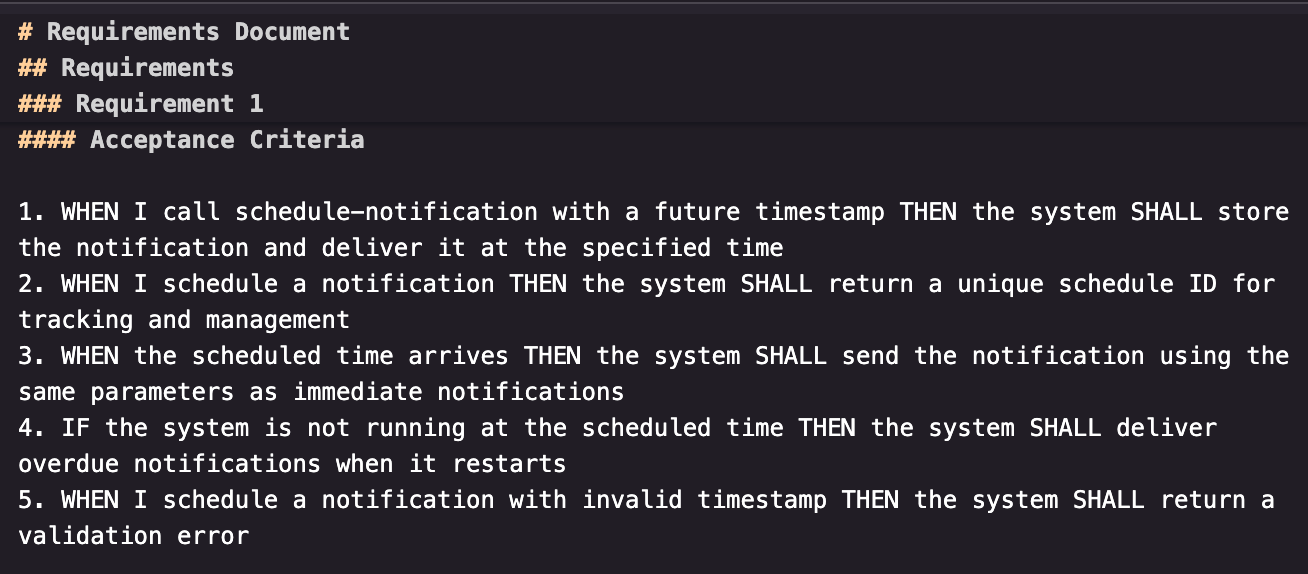

Looking deeper into the requirements document that was generated, I also noticed that it followed the same rigid structure pattern that the steering docs had done.

The risk with this rigid structure (like the steering documents) is that it relies on a single, omniscient reader to carry forward everything. There is no native persona-specific drafting. It would’ve been cool to see the requirements broken apart or built upon by a series of experts such as a “product manager” and a “software architect”.

This was becoming a recurring theme — which I will now refer to as “one persona to rule them all” or (OPTRTA) — or perhaps “Saurona” would be more memorable.

I was about to give up and move onto design when one last tantalizing feature caught my eye: a shiny REFINE button on the top of the requirements file. I hoped it might go through an interrogation or reflection flow. Instead, it just linted the doc ensuring that the WHEN/THEN/SHALL keyword format was respected.

Phase 3: design — it can draw some nice boxes!

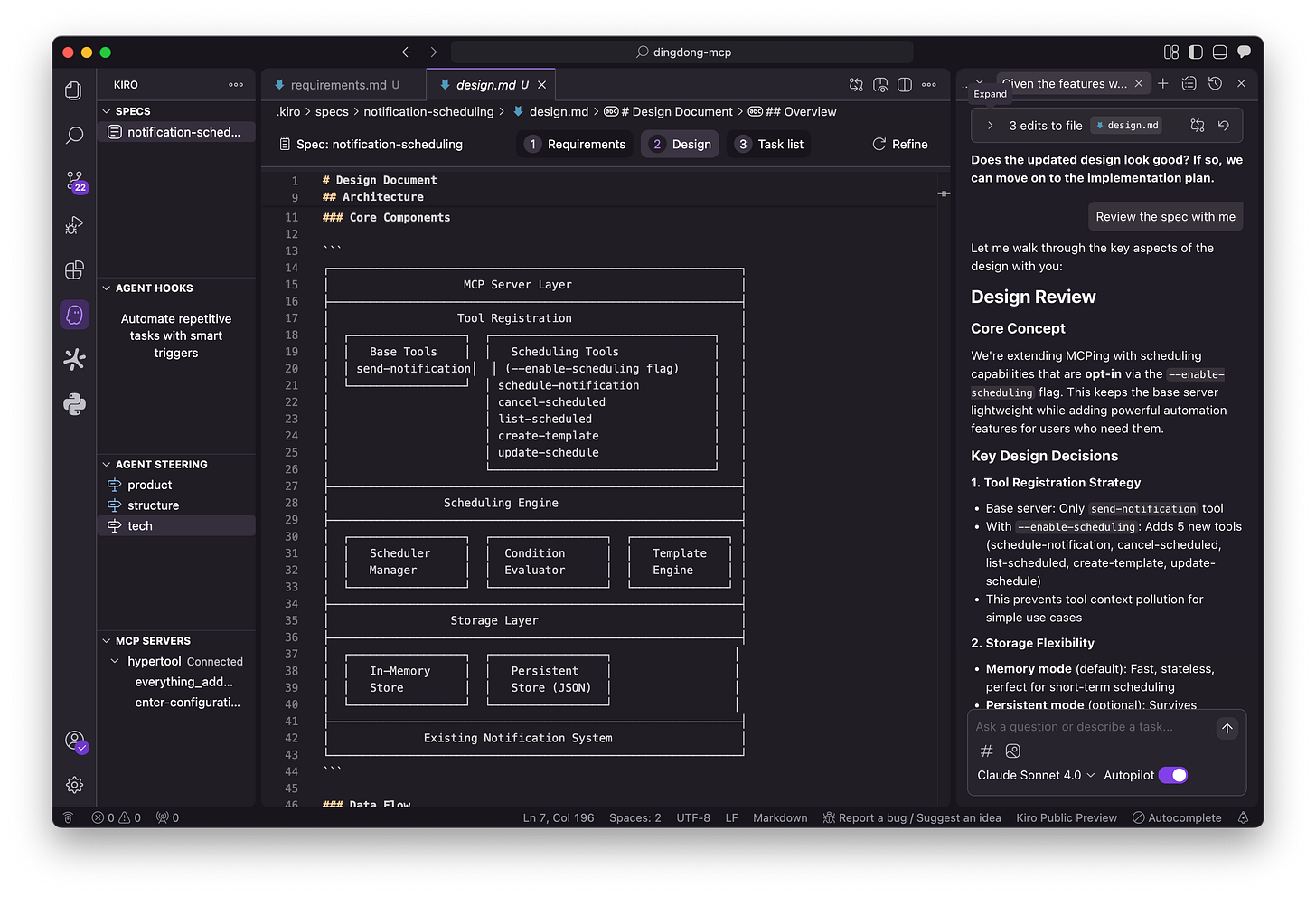

After requirements, Kiro marches straight into the design phase. Requirements, Design, and Tasks (the final phase), are treated like bolted on additions on a conveyer belt.

In one shot, Kiro generated an architecture diagram, a data-flow section, and outlined components and interfaces. This was impressive, but again the lack of a back-and-forth diminished the value of the final product. Where was the reasoning? The back-and-forth? If this were an engineer I was working with, I would expect them to suggest a variety of options, discuss tradeoffs, define responsibility boundaries of components, etc.

Kiro does give the option to “Follow Along” as it generates these artifacts but watching it do this is the equivalent of watching a printer spool rather than watching an intelligent engineer employ their faculties of reason and experience. This was probably the last place one could catch a shaky requirement or false assumption.

In a greenfield or toy project this kind of yolo design could work. However, yolo design in brownfield projects will necessarily compound technical debt.

Phase 3: task flow - ok this part was cool

One of the biggest challenges with requirements → design → tasks in claude-code is that there is no in-built framework for orchestrating a DAG (directed acyclic graph — basically a dependency graph) between tasks. In vanilla claude-code, the best it can do is have a “todo list” which is serially executed.

To get around this, we have used several frameworks such as claude-task-master. As I alluded earlier, we’ve moved onto using an internal task-orchestration tool that we’ll share more about in the future.

In contrast to claude-code, complex task orchestration a first class feature in Kiro. Finally, something it excels at. From the requirements and design artifacts, Kiro generates a series of tasks, visible to you in markdown and internally manages them with a dependency system.

Once these tasks are generated, Kiro can automatically start implementing them. It will stop and ask you for permissions to run bash commands, make tool calls, or call MCPs — the typical permission flow that we’ve experienced in IDEs and claude-code.

TLDR; Kiro does a good job of task generation, task-dependency management, and task execution.

Caveat: code-generation based on tasks is only as good as the context they were generated from — the artifacts of the previous phases. So while this execution is sleek, it inherits shaky foundations.

Models & Pricing — the final nails in the coffin

Even if you can forgive the rigid workflows and the “one persona to rule them all” mentality, Kiro still falls short on two fronts that matter most in practice: models and pricing.

First, the models.

Kiro only supports Claude Sonnet 3.7 and Sonnet 4.0— not Opus nor any OpenAI models such as GPT5.

This is a serious handicap. The whole premise of agentic workflows is that they depend on reasoning quality. If Amazon (sorry I meant Kiro) doesn’t have access to these frontier models, it will never be able to keep pace with claude-code or Codex.

Second, the pricing. A universally derided shortcoming of Kiro. Kiro charges on “spec” and “vibe” requests with a usage-based overage model. The delineation between these two types of requests is fragile. I mean what is a “spec” request? What if my spec is tiny and I have 500 spec requests which in actuality only use 30k tokens and 100 vibe requests which use 10k tokens? What if I had 1000 tiny vibe requests that only used 5k tokens? I would get penalized on a per-request basis rather than on model usage.

This feels like a deja vu of Cursor’s failed experiments which resulted in community outrage. Engineers don’t want to count tokens every time they hit “generate” — a claude-code like cool-down with resets of token allocation would’ve been preferable.

Which leads to the obvious question: why would anyone bet their daily workflow on a tool that’s underpowered, overpriced, and outgunned

Parting thoughts

I was looking for that same “iPhone moment” when I booted Kiro. Instead, it felt like unwrapping a birthday gift at twelve only to find a book when you were hoping for the videogame you’d pined for all summer.

The one thing Kiro did clarify for me is that context engineering is the whole game. Without it, no agentic IDE will scale. And right now, Anthropic is the only one of the “big three” (Anthropic, OpenAI, Cursor) shipping tools that make context engineering truly usable for developers.

At toolprint.ai we’re committed to pushing this further — building tools that improve your context and reduce pollution. Explore what we’re building on GitHub, or take a look at hypertool-mcp, our MIT-licensed project for giving your apps the right mcp tools without the baggage.